The research on Arab knives suffers from the same issues that are commonly found in research on Arab swords, daggers and armor. The limitedness of the material to study and poor documentation are some of the main challenges. This article attempts to categorize Arab knives based on region, focusing on the Levant and the rest of the Arab peninsula.

The Levant

Knives produced in the Levant encompass the modern borders of Lebanon, Syria, Palestine and Jordan. The countries of the region historically exchanged arms through movement and trade. This explains the many shared features between their productions. Also, the Levant is influenced heavily by surrounding regions and its tumultuous history shows that influence on its arms and knives are no exception. Its own history and religions as well, are the main influence and that can be noted in the symbology on the items such as ones noted on Lebanese knives and daggers (as well as examples from other regions within the Levant)

Lebanon for example, is known for Jezzine knife production which according to the Jezzine Union have been established in 1770 (1). For the most part, the producers of those knives are Christian craftsmen who often use Christian symbology and biblical references.

One of the main noticeable details about Lebanese daggers is the Phoenix or the crane design of their handles. Often also describe as Tair (bird in Arabic) but likely the design traces back to ancient crane symbology that existed in the region before Christianity. The craftsmanship of those handles is shared with double edged daggers as well of earlier age.

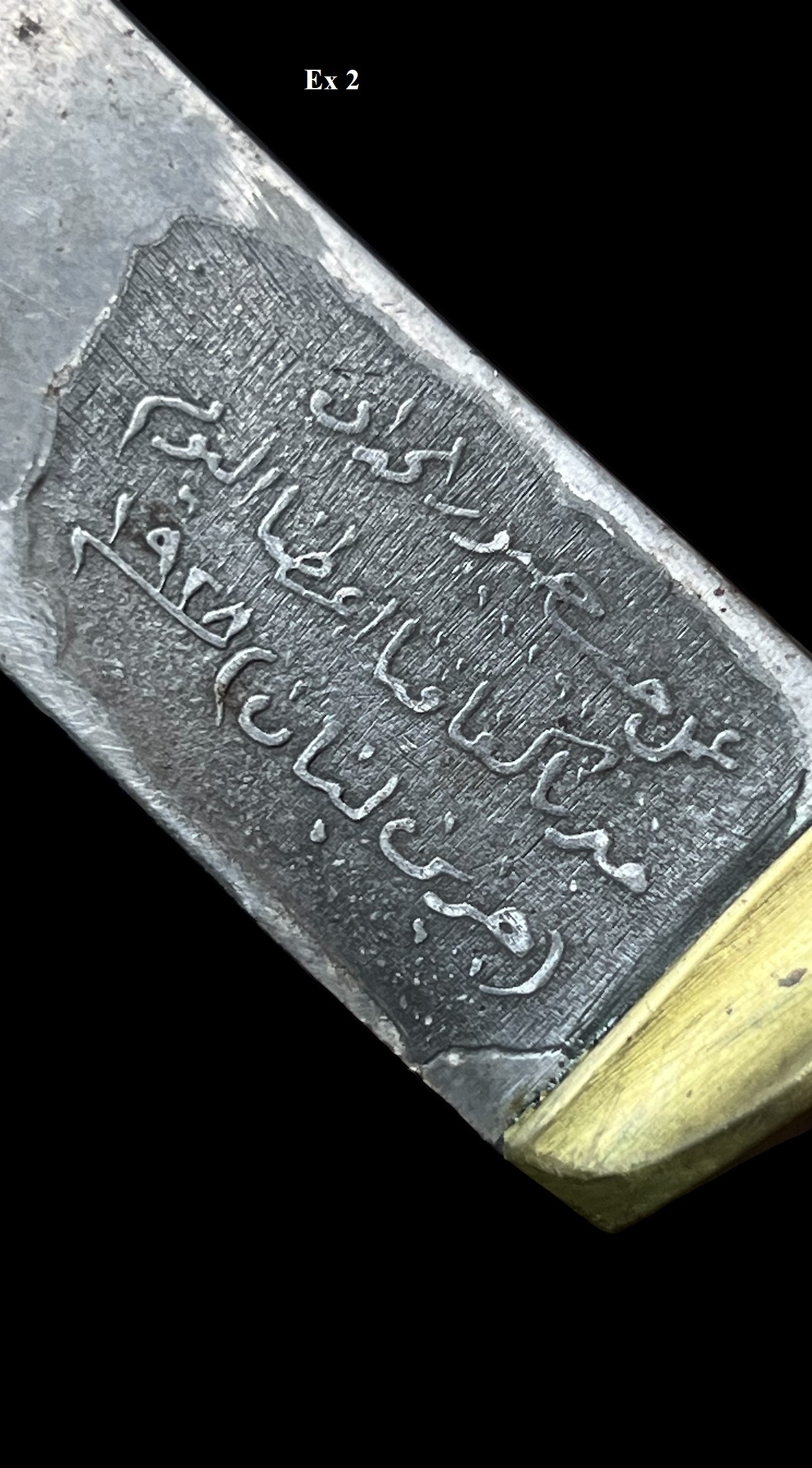

Ex.2 contains both the maker’s name which reads Habib Jabur alHaddad who belongs to Haddad family which to this day produces knives along with several other families. The second line references the Lord’s prayer from the book of Matthew which says “Give us our daily bread” while the bottom line contains the location; Jezzine, Lebanon and the production date in Gregorian marked 1928. Both Ex.1 and Ex. 2 have the same design with varying hilt quality while using the same material. But in comparison, Ex. 3 is likely of earlier late 19th century production as similar brownish horns akin to horns of Iraqi water buffalos were found on older pieces while later productions such as Ex.1 and Ex. 2 use a darker denser horn. Modern production moved from the use of organic material to the use of plastics and fabricated mother of pearl along with soft metals such as brass and copper.

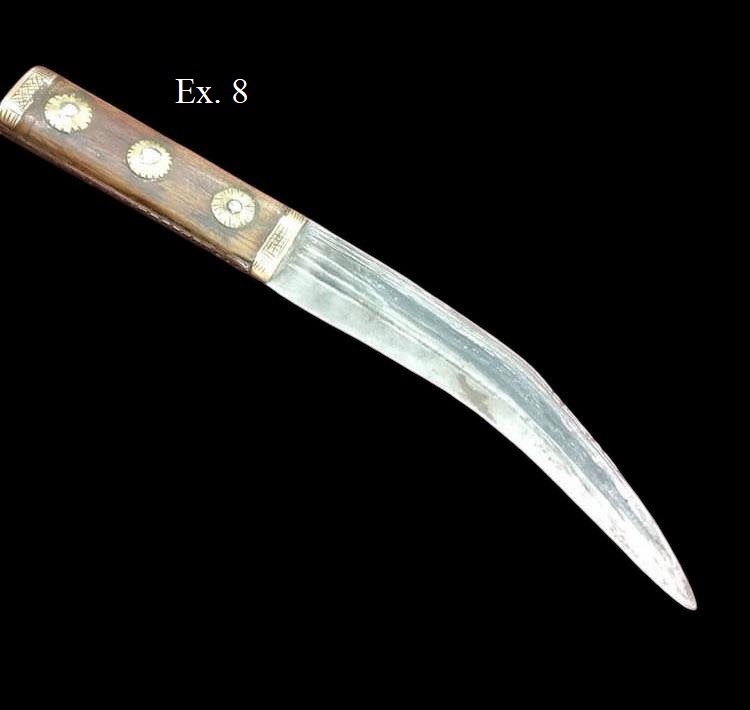

Syrian made knives can be tougher to identify due to their similarity to Turkish examples and the reuse of examples from both Turkiye and Persia with minor additions added to them in Syria. Though their craftsmanship can be noted in the construction of distinct scabbards and blades. Hilts vary, with some easily recognized due to their mosaic like construction following the same method of well-known majdali daggers. Perhaps what can be considered a standard form of Syrian knife hilt construction can be seen in Ex 4 which follows a construction method very similar to Persian kards with a thick tang and two bone or horn slabs. Ex 6 is socketed using layers of horn and bone and a brass bolster. Brass sheet scabbards like Ex 5 are common and so are the koftgari decorated iron scabbards commonly made in Damascus.

Their blades are well made will complex fuller construction; and it appears that they preferred softer blades for easier sharpening, a choice also made in Majdali daggers as well.

Jordan and Palestine are well known for the production of the shibriya, which has both a utility purpose and a decorative purpose. Its edge designed to be able to easily slaughter sheep and camel and to prepare a meal. Infact, one of the most noticeable oddities about shibriyas is that often they come coated in animal fat which can be rancid and damaging to scabbards if left for decades until they arrive into private collection. Yet even though shibriyas fulfill the purpose done by a knife, a few examples exist of knives made with handles and scabbards made in standard style commonly found on shibriyas. Though a high-quality example of a knife made in Acre, Palestine exists in the private collection of Saeed ibn Hmooda with a wootz blade, dated 1219 Hijri, with niello silver mounts signed with what appears to be the owner’s name (Mohammed Kamel al Shami) fair to note that the knife contains a slot for belt wear in the same style used on shibriyas, showing the influence and method of wear, as well as possessing the Ottoman emblem, giving context to the time of its production.

Central Arabia and the Eastern Province

Crudely made knives commonly called Khusa, made in very similar fashion in both central Arabia and the Eastern Province, where knives are viewed as strictly a utility unlike the khanjar which can be seen as regal and more decorative in its purpose, while retaining its original function as a weapon of self-defense. Thus, this affects the way knives are constructed, often commonly found to be simplistic using steel from springs and files with rudimentary handles using materials such as plastic, bone, wood and sometimes local horns. Their appearance reflects their work like nature in comparison to the often-attractive construction of swords and daggers made in said regions. Terms used to describe this type of knife differ, with people of the same region calling them Khusa, Shafra and khadama. Those terms are the most common, though Abbas Mohammed al Eissa, a Saudi researcher also adds the terms mebrah, maklamiya and huwaithriya. (2)

In alHasa, the knives are made by the local smiths who also produce well-made farming tools. While in Nejd, it is said that those knives are made by a group called Khlowah who are traveling craftsmen who often have temporary settlements at the borders of Nejd where they work in Dallah repairs, knife making and knife sharpening.

Expanding into a wider Saudi Market, knives made in Southern Nejd (southern central Arabia) all the way to Najran, such as ex.10 tend to have high similarities to knives made further north and east. This is likely due to the nature of its bedouins being travelers between those 3 regions and having intertwined history and trade centers.

Hejaz

Knife users in Hejaz focus on quality imported blades, especially German Herder knives and other, quality European knives though German Solingen made knives are the most prominent. Those knives imported heavily by traders such as Habibullah Kashghari (3) gained prominence as effective, durable, edge retaining knives and such, it is quite common to find them worn to this day by Hejazi hunters who often spend days in the wild, sustaining themselves with their hunt for which they use those knives to slaughter and butcher.

An interesting feature for Hejazi knives is the use of large scabbards called Lahaaq that are mostly produced by Hejazi women for their family members (some though are made and sold in a limited local market). Lahaaq in the past was decorated with silver or lead beads called Qashaash. Modern examples use synthetic and plastic beads.

Oman and Zanzibar

Omani and Zanzibari knives share a common heritage, with their silver/gold work often identical. The usage of knives and their wear is mixed with the khanjar, where the knife is fitted behind the scabbard ready for daily use, such as thabiha (4) and the cutting of food and other daily needs. Though they do follow the pattern of being a utility, the knife makers often decorate the handles with skillfully made silver wires in geometric patterns and sometimes capped with floral decorated caps and bolsters.

The blades are often imported, with English shear steel blade highly preferred over the locally made versions. Older examples imported from India are also present, with some likely made of crucible steel.

Knives made in Zanzibar can differ from Omani examples in the use of high quality ivory with gold/silver inserts in a fashion much similar to the Zanzibari Nimcha. (5)

Yemen

Yemeni shafras are well represented in writings done by Stephen Gracie and other interested researchers in the field whose work is proven to be invaluable in understanding the complex history of Yemen and its much appreciated artworks. One of the first things to note though, is that Yemen extends its interaction with India not limiting it to the import of blades only as is other Arab regions; but that Yemenis also import fine silverwork daggers, swords and knives from India that is often described as Indo Arab craftsmanship.

Quality shafras such as the examples shared employ high quality silver with fine engravings in art style like saifs. Their blades often forged with filing work done to their spines to add a decorative element to a utility item. Yemenis use files to make local version of the downwards curved knife but also versions made of pattern welded steel and imported European knives are used as well.

Ivory and horn examples are also well documented though the usage of silver examples is still present to this day due to the ease of maintenance of the material and the ease of its production and availability.

another version of the Yemeni shafra comes with locally made handles (ex no.) with varying designs such as ones with handles of a form similar to Yemeni karabelas often stamped with maker’s names at the back or engraved with the maker’s name often in large clear letters.

North Yemeni examples share a common design with Southern Saudi examples, mixing metal and horns. Their blade design differs in the proportions of the blade focusing on a wider tip and T spine construction with thinner, razor like blades.

Arab knives deserve to be highlighted; showing their characteristics and often unique attraction. Although varying from region to region, a common shared between them is their purposefulness outshining their decorative side while still maintaining enough character and display of their craftsmen’s skills.